Slightly obsessed with GPX

- Table of contents

- Trackbook

- trkpt

- Hardware upgrade

- NMEA ingest

Trackbook (§)

In December 2020, I downloaded an app called Trackbook by author y20k. This records your GPS position while you walk, hike, drive, or bike, so you can see where you went. GPX is a standardized XML format for storing these tracks.

There are quite a few Android apps for recording GPX files, but I always found Trackbook to be the most pleasant to use for both its aesthetics and simplicity. I submitted some bug reports and even stumbled my way through Android Studio enough to make code changes and submit a few pull requests, which were merged.

GPX files are helpful for contributing edits to openstreetmap, because you can more accurately trace out paths that might not be clear in aerial photos, and you can publish the GPX for other mappers to reference as well. You can also use the GPX to know where you were standing when you took a photo of a point of interest, so that you can position the POI more accurately on the map. This is better than relying on EXIF geotagging in some cases.

Besides being useful, I think GPX recordings are fun. I don't need a GPX to help me map out a sidewalk, but I record my walks anyway because it's cool to see where I was at some time in the past. Much like a photograph, a GPX recording is an artifact by which to remember the day.

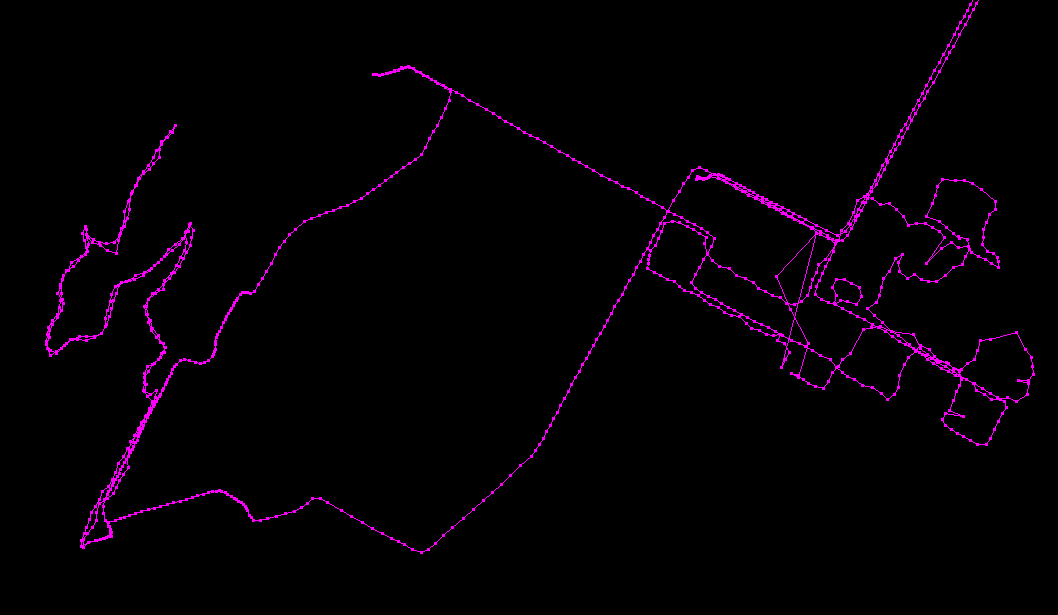

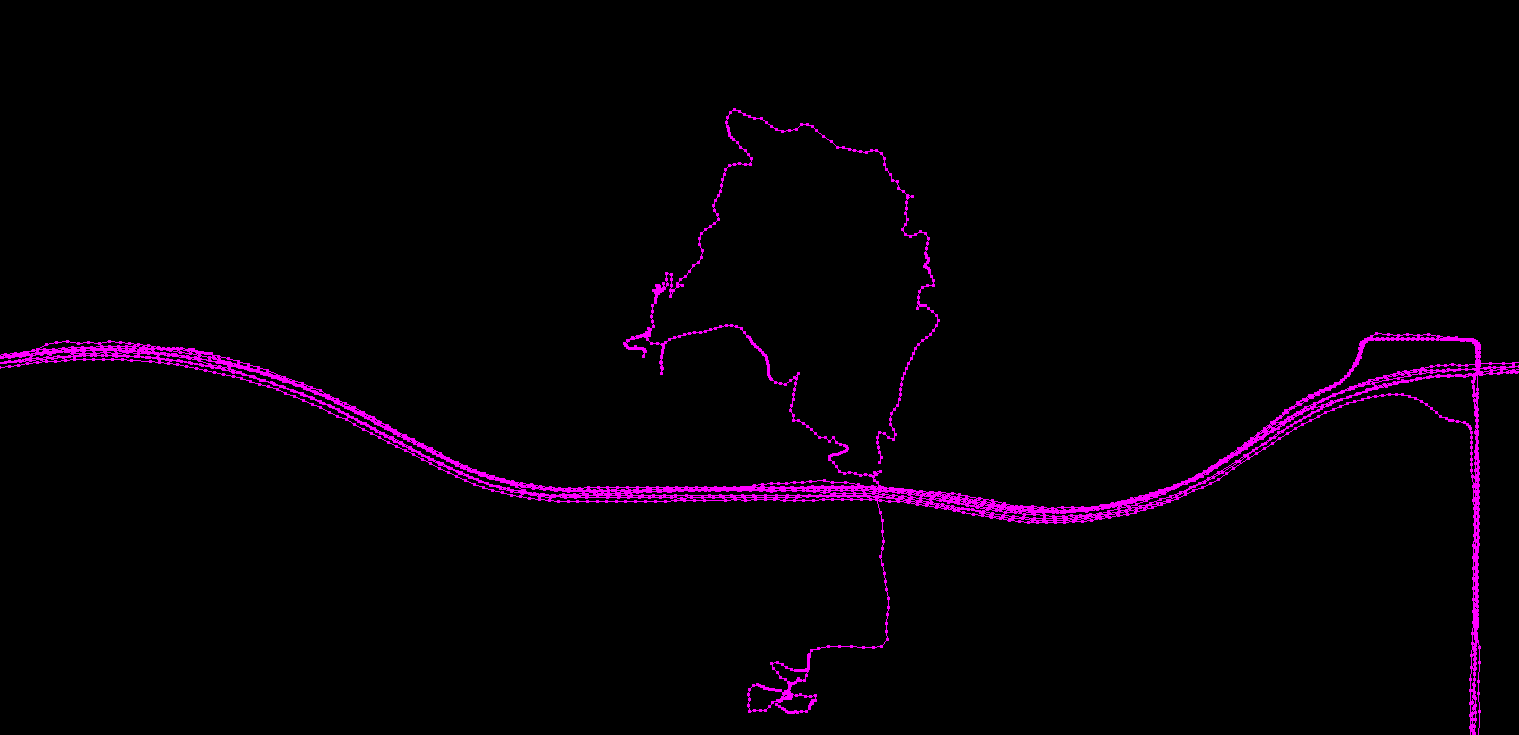

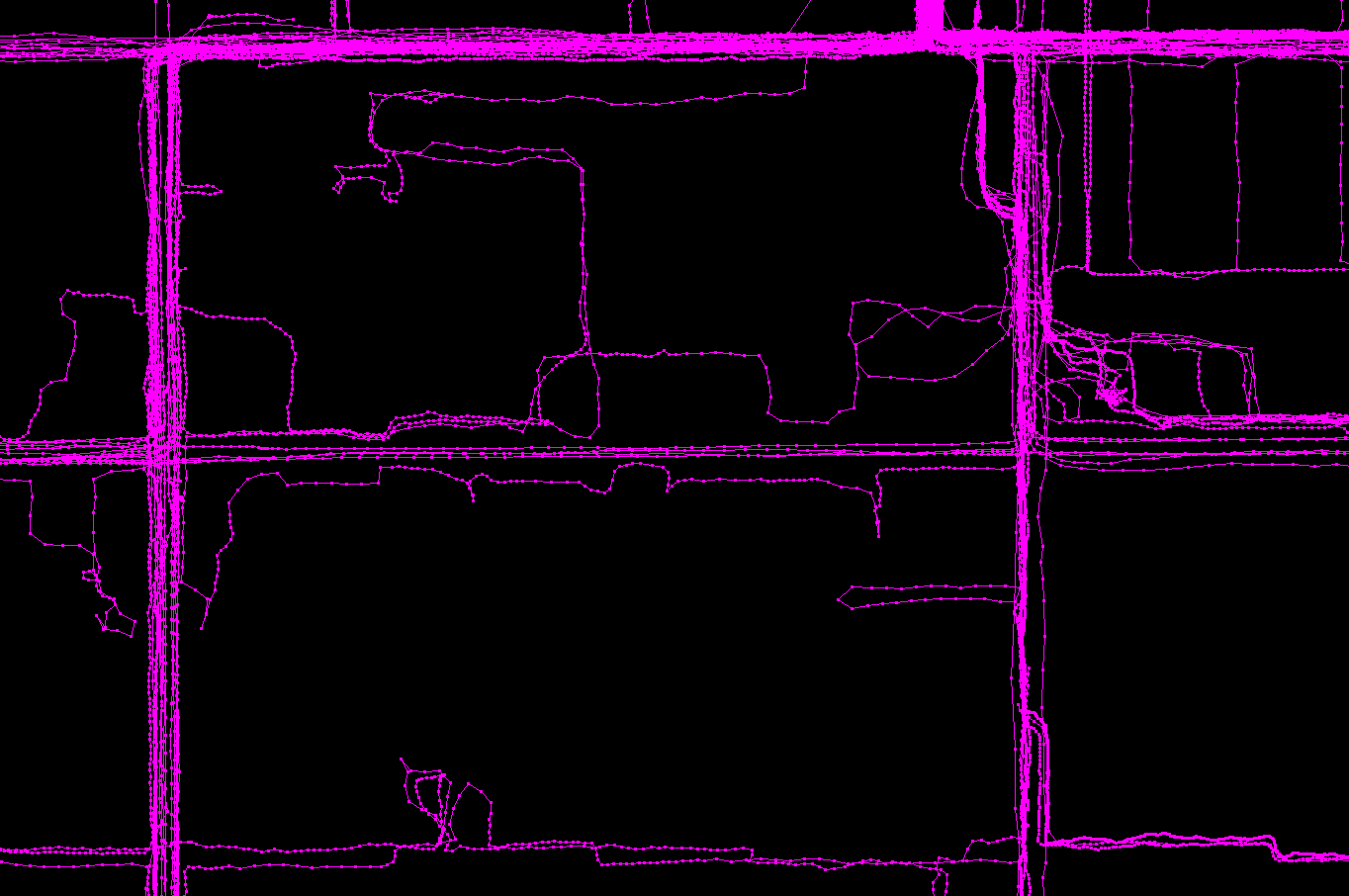

Now that I've recorded more than 100 GPX files, I have become quite fascinated with dumping all of them into JOSM and seeing every single track overlaid on top of each other. The rivers of common routes and spiderwebs of distant destinations are very pretty. I zoom in and out, recognizing locations by their pink periphery against a plain black background.

In March 2023, I became seriously interested in the idea of recording GPX 24/7. I started to think about how awesome these pink rivers and spiderwebs would look if every single path were lit up. Until now, I had primarily used Trackbook to record deliberate outings and special trips. And that's great, but it meant that my track collection mostly showed little disconnected bubbles of places I've been to only once or twice because I didn't typically record day-to-day events. Also, if I was driving to a location to hike at, I'd intentionally wait until I got there to start recording because the drive would dominate the statistics like distance travelled and average speed. What's worse is that I would sometimes forget to start recording at all, and I'd miss the whole day. I knew that micromanaging the start and stop time of each recording for the purpose of statistics was silly, and that it would be better to collect as many trackpoints as possible and then make sense of it in post.

Initially, I was concerned that if I recorded too many tracks, the boring commutes would drown out the interesting trips, but it turns out that boring tracks are actually interesting too, given time. Seeing how easily JOSM handled the quantity of points I loaded into it gave me confidence that I should proceed. It is probably better to regret having too much data than to regret not having it.

However, the data structure and user interface of Trackbook are not geared toward 24/7 recording. It is designed for recording outings with a distinct start and end, and this presented me with some friction in using it the way I imagined.

trkpt (§)

I sat on the problem for a very long time, and then I finally decided to make a fork of Trackbook called trkpt that takes the data model in a direction more suited to my goal. This is my first time forking someone else's project and republishing it with a new name. It makes me feel somewhat guilty, or rude, but it's ok by the license and I'm enjoying the freedom to make this work just how I want it.

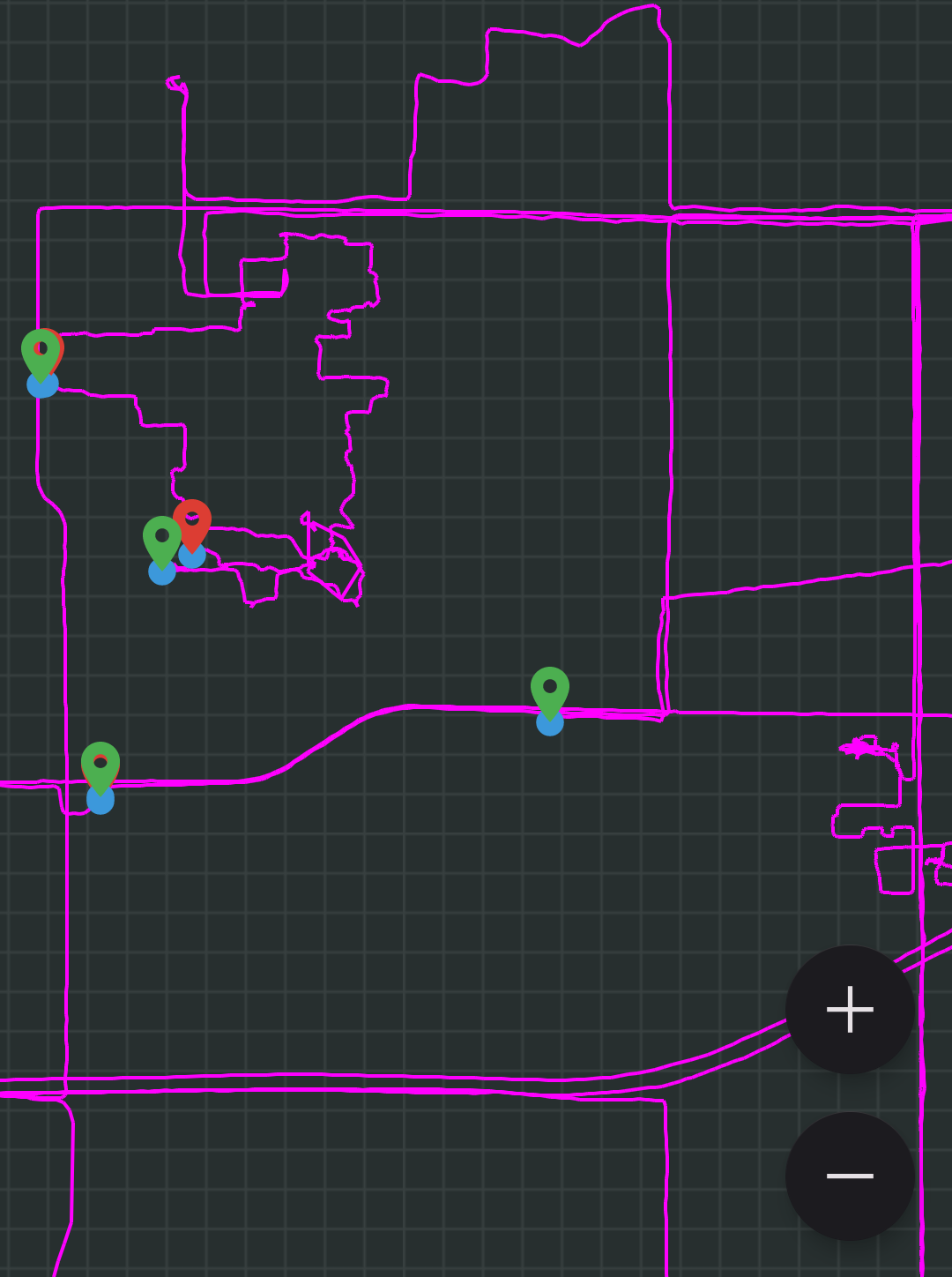

Basically, I swapped out the JSON-based file storage with an SQLite database, and removed the entire concept of "Tracks" as a stored object. Instead, the database of trackpoints is queried on the fly to produce tracks with any start and end time you want, which you can export as GPX files. This also opens the door to JOSM-style megarenders and geospatial queries like "what day was I here?". I even made it pink.

I also added "homepoints", which are points you can put on the map around your home or workplace so that trkpt does not record any trackpoints there. Due to GPS's natural inaccuracy and drift, which is especially bad when you are indoors, you tend to get large clouds of points around buildings if you leave the recording on, so homepoints eliminate that.

In the first draft of this article, I wrote:

I do not literally run trkpt 24/7 just yet, because my instinct for optimization doesn't like the thought of leaving the GPS at full power all night long and at work, capturing tens of thousands of fixes that are immediately thrown away; or worse, struggling to capture a fix at all. It is hard to shake the somewhat superstitious feeling that it would have a negative effect on my phone's long-term battery lifespan. Maybe I will find a balance that reduces power consumption near homepoints without sleeping the GPS so much that it is late to capture departures. These mental blocks are the only thing in the way of me running trkpt all the time, so the code changes themselves have been successful, I think. I am still starting trkpt when I wake up in the morning and turning it off at work. But for day trips on weekends I record the whole day with no stress, thanks to the flexibility of the new data model.

But, I sent an email to y20k to share my work with him, and he suggested using the device's accelerometers to improve the sleep/wake cycle and conserve battery. This really helps!

Android provides a significant motion sensor which, while implementation surely depends on the manufacturer, is meant to be used in low power scenarios where a latency of several seconds is acceptable. When we are near a homepoint, we can reduce the polling frequency of the GPS to once per minute, or perhaps five minutes. As soon as motion is detected, we can wake it back up to full power, so that by the time your shoes are tied, your fix is hot again.

When I am at work, my device struggles to acquire any GPS fixes at all, so trkpt can't even know if I'm near the homepoint. In this case, there is no benefit in reducing the polling frequency of the GPS. If you ask Android for one location per minute and it has to struggle for several minutes to get a single fix, then you're not saving anything. The GPS burns a lot of energy in this state and it's better to turn it fully off. This means we are placing a lot of trust in the motion sensor to restart the GPS, so I will see how it goes and continue experimenting with the balance between all these features.

Anyway, the code is the easy part. Now I have to do the hard part which is actually going out to interesting places more often and turning the world pink.

Thank you y20k for making Trackbook!

Hardware upgrade (§)

I have been using trkpt to record every single day for the nine months since this article was first published — a total of 265 tracks! On the whole I feel it has been very successful.

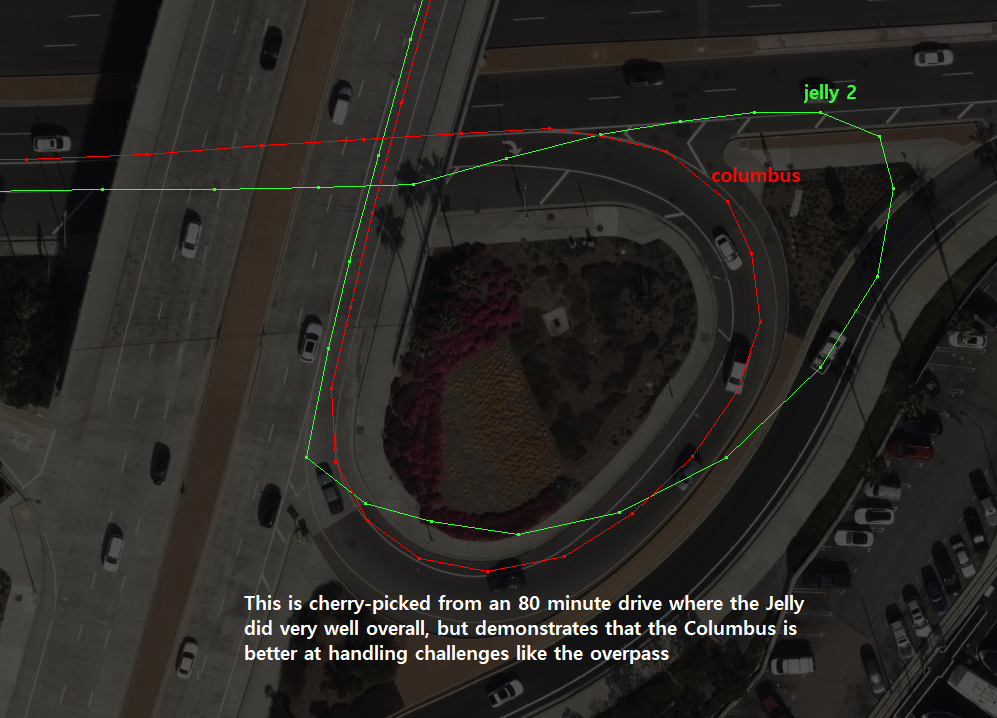

I have been using a Unihertz Jelly 2 exclusively for trkpt. I had bought it for another reason in 2021 and repurposed it as a unitasker for this role.

But, having experienced both the advantages and disadvantages of using a cell phone as a 24/7 logger for nine months, I decided it was time to buy some made-for-purpose hardware. After quite a bit of research and quite a lot of hemming and hawing, I finally bought the Columbus P-10.

It took me almost two months of indecision before I finally caved. The singular cause of this indecision was the fact that the Columbus uses Micro-USB instead of USB-C. In my opinion this is unforgiveable in 2023 at the price of $240, but I can still use it without forgiving it. A separate-beds kind of relationship. Now I need to keep an additional cable on my desk and in my car — a cable I thought I was done with. There are simply no other competing products on the market in this form factor doing USB-C, the closest being the Bad Elf Flex Mini which is a big chunky device for surveyors.

Here are the main problems I encountered with the phone that pushed me to upgrade:

Fighting the device: Android has heavy eyelids. All it wants to do is doze. Doze most often leads to missed points during car trips that are longer than about 45 minutes. The phone's accelerometers keep the device out of doze while you are walking, but there are not enough g-forces for this in a car except in particular life-threatening circumstances. Battery-saving exemptions, foreground notification services, and wakelocks are not enough to convince Android that you really do want to keep trkpt running the whole time. I think what's possibly happening is the app itself is staying awake, but the location subsystem is going to sleep and so trkpt receives no data.

Maybe if I rooted the device I could fully disable doze, but I'm afraid of bricking it and I don't want to go down that road. If the phone is plugged into a charger it will stay out of doze forever, but this option is not available when I am a passenger in someone else's car. I can also hold the device out with its screen on the whole time to prevent doze, but then I have to explain my weird interests to other people so I don't like doing that. It suffices to say that this anxiety / micromanaging around doze is not in line with my goal.

Besides doze, I also encountered an occasional operating system crash with the phone. Maybe three or four times this year, I took the phone out of my pocket to find that it had reboot itself. That's still pretty impressive, all things considered, but the Jelly does a few other things that make me doubt its software stability. It's a cool device, but when a company as small as Unihertz makes as many different models as they do, you just know they're cutting corners, and software is definitely one of them.

Cell phones don't really want to be unitaskers, and while it is possible to whip them into shape, I get tired of doing so much whipping. I'd rather have something that's not a fight.

User error: From time to time, I have stopped the trkpt recording, either to do some database edits or to reboot the phone or whatever, and forgotten to start recording again. My biggest blunder was when I edited my trkpt database file on the computer without waiting for Syncthing to fully synchronize with the phone, which caused a Syncthing conflict. For five days, the phone continued recording to whatever file handle it still had open, but none of the data actually got saved, and I didn't notice until I wanted to do an export of the week. To help prevent this from happening again, I went ahead and changed the trkpt code to re-open the database handle when resuming a track.

Track accuracy: One of the reasons I used the Jelly for trkpt instead of my primary LG phone is that the Jelly's positional accuracy is simply better, and I was always pretty satisfied with it. However, there was still room for improvement:

The Columbus solves these problems because it is single-minded and never stops recording, and the flashing lights confirm it is working at a glance so I am unlikely to leave it off by accident.

For what it's worth, I can confirm that battery life was never a problem with the phone thanks to the accelerometer-based sleep/wake system and homepoints.

The manufacturer's claim of lane-level accuracy is well earned. Assuming that Bing's aerial imagery is aligned more accurately than my equipment, I can see that although my tracks don't always run straight down the middle of a car lane, they are within the lane, and lane changes are unambiguous.

Undeniably, the phone has some advantages which I am sacrificing here:

Syncthing: On the phone, I have set Syncthing to run whenever it is plugged into power. So as soon as I get home and take my stuff out of my pockets, my trkpt database is synced to my computer. With the Columbus, I have to plug it into my computer and copy the data over (more on this below). I know this sounds the same, but to be more clear, I like to charge my phone using a desktop power adapter instead of plugging things into my computer, to keep my computer free of dangling wires and snag risks. And did I mention I have to use a Micro-USB cable?

Immediate review: Because the Columbus does not have a screen, I can not look at my track until I get home. Besides the entertainment value of watching the line draw in real time, the immediate review was sometimes helpful if I wanted to ask "where did I start?" or "which path did I just take?". Of course I can still run trkpt on my normal phone if I really think I'll need to do that.

Customizability: The great thing about open source code is you can just change it whenever you want. All that stuff about homepoints and sleep behavior can be customized for trkpt, but the Columbus is not open source and you have to make do with the options in the config file. Fortunately it is comprehensive enough, offering a minimum movement speed to reduce stationary point spam, and accelerometer-based move-to-wake.

I've had the Columbus for two weeks now and so far I think the upgrade has been worth it.

NMEA ingest (§)

Earlier, I said that it's "better to collect as many trackpoints as possible and then make sense of it in post", and now I'm being held accountable for my words. The Columbus gives you the option of recording straight to GPX files, or to NMEA sentences. The NMEA format is as close to raw as the end user can get, and even disables some of the in-device filtering options. Naturally I picked that.

The Columbus does not have anything like my "homepoint" feature, which is understandable, so every day I come home with huge clouds of point spam at my workplace (partly because it is better at capturing points indoors!), which I delete before exporting to GPX. I do not want to be in the habit of turning the device off when I arrive, because I'm certain I'll forget to turn it back on again from time to time. Collect everything and make sense of it in post.

So, I'm on the hook for doing whatever kind of filtering or pruning I want to do as part of my intake process for the NMEA data.

I started by writing a Python program that detects the mounted storage device, finds new NMEA files, and inserts the points into a trkpt-format SQLite database. This means the ingest is basically a one-click operation. It could maybe become zero-click if I detect the USB device with a scheduled task.

I used pynmea2 to parse the data, and had to combine the GGA sentences which contain number of satellites, altitude, and HDOP but no date (why?!); and the RMC sentences which contain the date.

During this import, I do some filtering to remove points I don't want, but I always keep a copy of the source NMEA file so I can go back if I ever change my mind. I could add a few more checks against homepoints, but I haven't yet. You see, one of the weaknesses of the homepoints is you have to give them a large enough radius to swallow up the stray, low-accuracy points that the device generates while you are indoors, but this radius winds up being so large that you lose the legitimate, high-accuracy points of your approach to the building and your movement in outdoor spaces near the building. I want to enjoy those for a while before I start filtering them out.

Then, Syncthing syncs that database over to my normal phone, and that's where I use the trkpt app to delete any more points I don't want and export to GPX. I know that sounds kind of stupid, and I would like to make a PC program for doing this instead, but that kind of GUI with pannable/zoomable points is not something I know how to make at the moment. Someone made a tkintermapview widget, but the framerate is not very good and I don't think Python is the right tool for this job, unfortunately.

- Add Hardware upgrade section.

- Replace github links with git.voussoir.net.

- Saving power with accelerometers.

- Add obsessed_with_gpx.md.

If you would like to subscribe for more, add this to your RSS reader: https://voussoir.net/writing/writing.atom