Download your podcasts

- Table of contents

- Introduction

- Downloading

- Tagging

- Cutting ads

- Listen & enjoy

Introduction (§)

Over the past year or two, more and more podcasts have been moving to Spotify and pulling their material from their other outlets. This is because Spotify wants to pump up their subscriber counts and is offering cash incentives to podcasters for exclusivity. The only situation in which this can possibly be interpreted as a benefit for the listener is when the exclusivity deal literally saves the podcast from going bust, and even this has caveats. Any other messaging that depicts Spotify-exclusivity in a positive light is pure spin and marketing, as the deal invariably removes control and choice from the listener. You can ignore the "oh, but Spotify's not that bad" crowd, because that's not the point. The point is that being corralled into Spotify is bad, and the same would apply to any other exclusive distribution point no matter how technically good it is.

Not to mention, as with any other material on the Internet, every day that passes is a day your favorite show might disappear for any number of reasons. You should also download your favorite Youtube videos and forum threads, too, but let's save that for another article.

Podcasts are often distributed as 128 kbps mp3 or thereabouts. At this bitrate, you can fit 100 hours of audio in 5.5 GiB. Just do it.

Downloading (§)

I am actually a bad ambassador for this kind of thing, because I like writing my own scrapers and downloaders, which most people won't want to do.

Let's start here: the podcast culture has traditionally used RSS for publishing episodes. Until recently, I never had a use for RSS, but now I see it as an important open format in the fight to keep data out of walled gardens like Spotify.

At this point, you can either search the Internet for "RSS podcast downloader" and find a pre-existing software solution to this problem, or you can continue reading and see how I do it. As you'll find, the nature of RSS does often require getting dirty and putting in some extra labor.

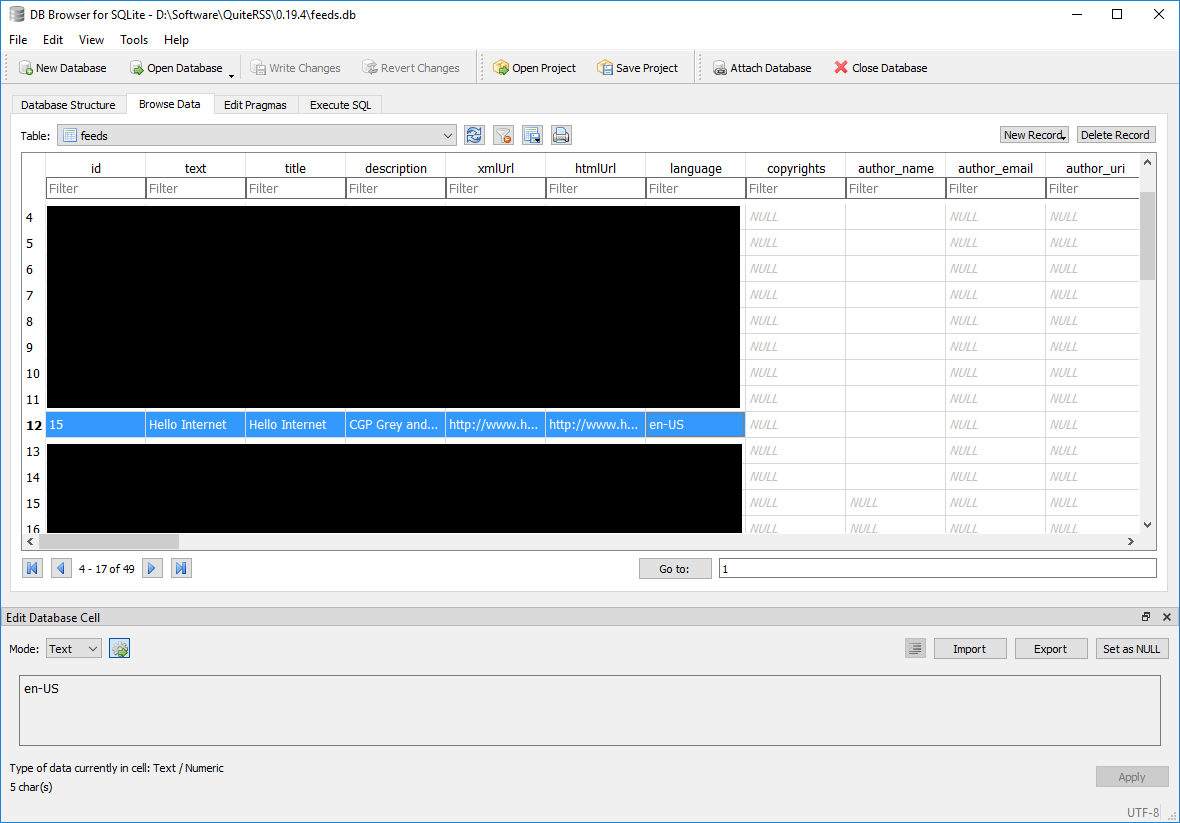

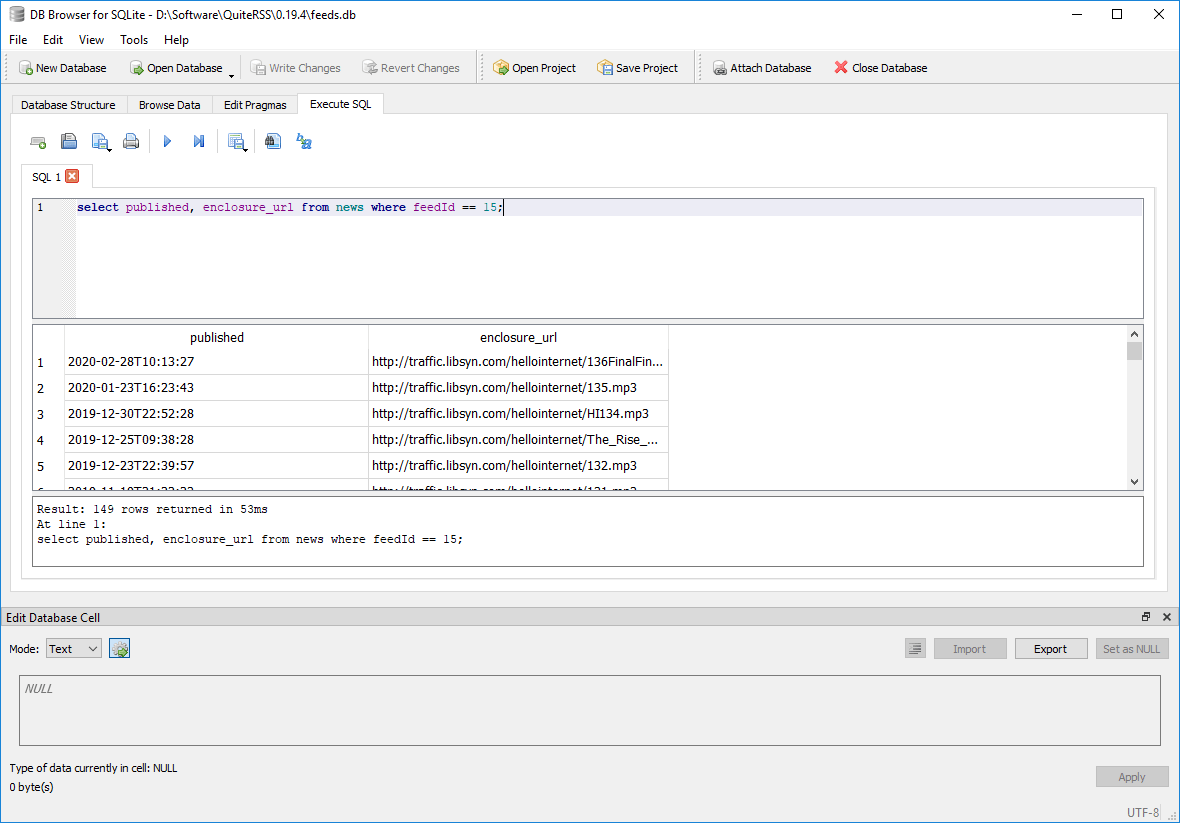

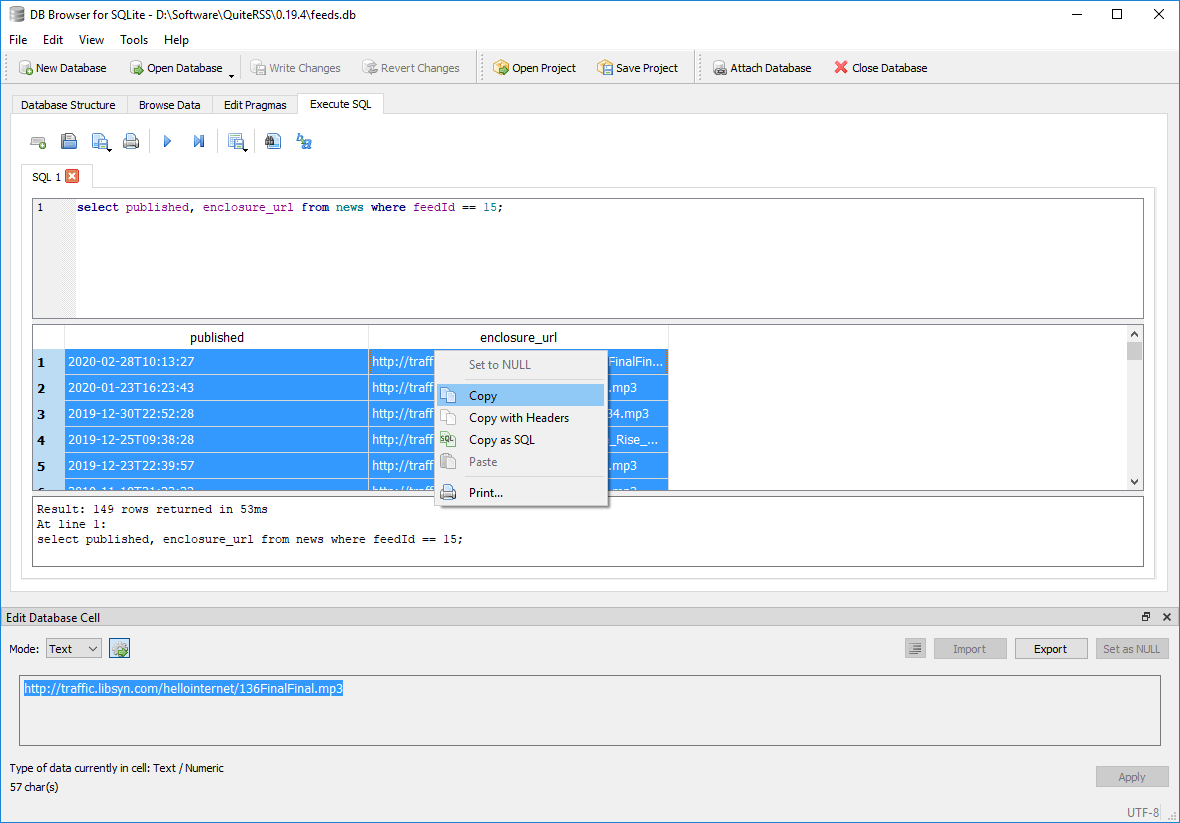

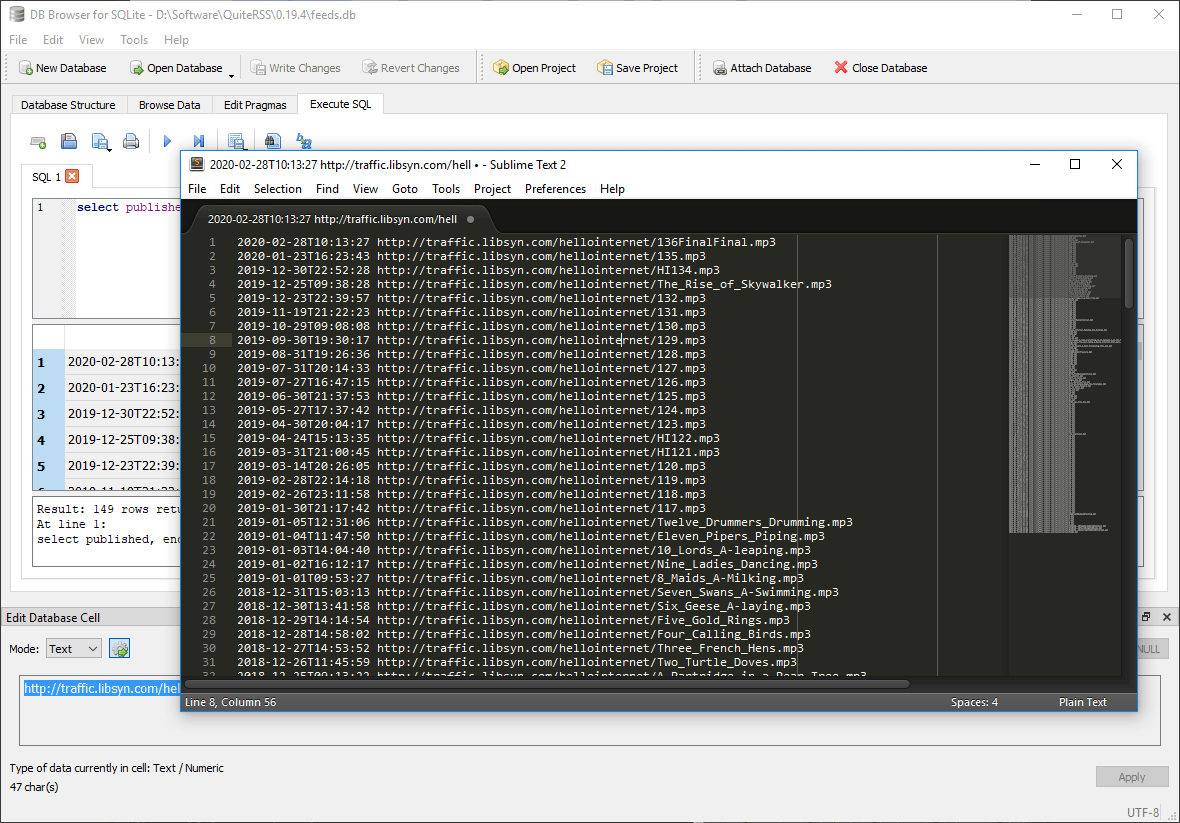

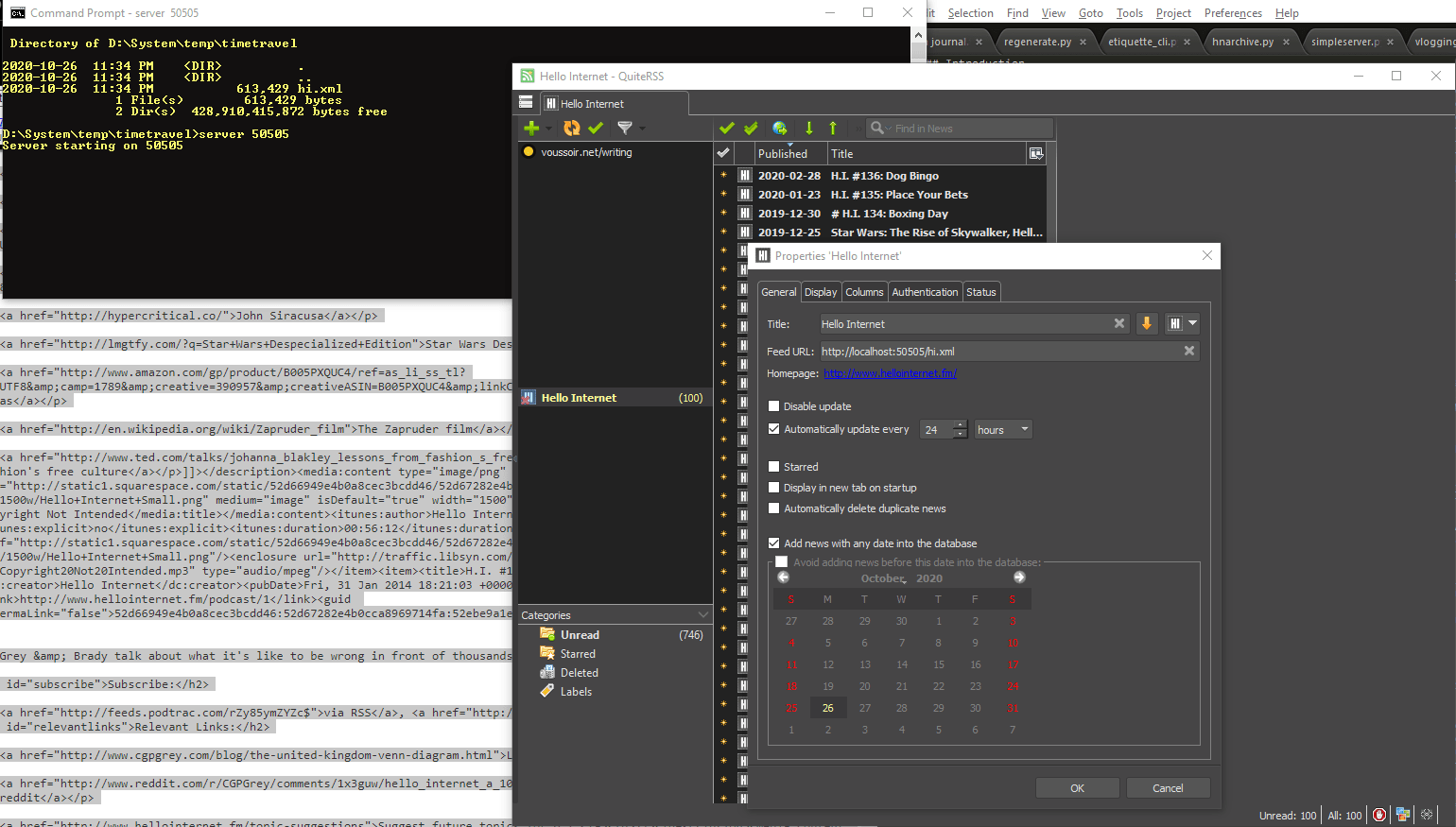

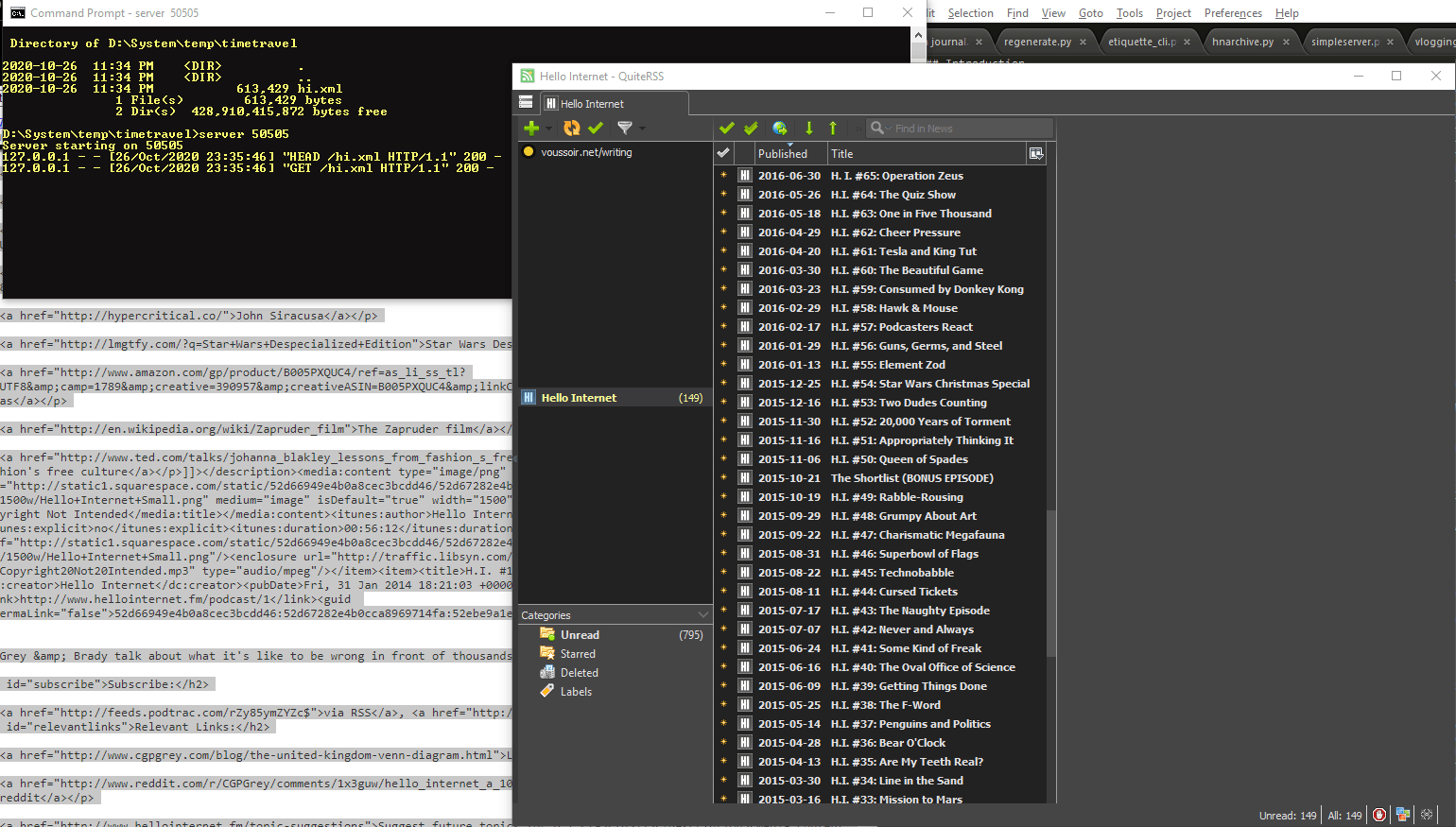

With no background experience in RSS readers, I tried QuiteRSS and have been happy with it. QuiteRSS uses SQLite to store the feeds and news items. With a tool like sqlitebrowser, or just the command line sqlite3, it's then trivial to get the published date and enclosure_url fields which I then throw into my own threaded_dl.py by preparing a file that looks like:

https://example.com/episode1.mp3 Podcastname 2015-10-31.mp3

https://example.com/episode2.mp3 Podcastname 2016-12-25.mp3

https://example.com/episode3.mp3 Podcastname 2017-04-01.mp3

https://example.com/episode4.mp3 Podcastname 2018-05-05.mp3and calling threaded_dl links.txt 3.

To be clear, I only do this for the initial download of the historical posts. After that, when new episodes are released, I just right-click & save file.

However, you'll find that many or most RSS feeds don't contain the entire history of the show. Squarespace, for example, only publishes the 300 most recent items in an RSS feed. Why? Because that's the number Apple uses and apparently it's easier to follow Apple's lead than to realize that RSS is an open format for a variety of consumers. I have seen other feeds that show only 10 items, which surely must be a result of poor configuration [1].

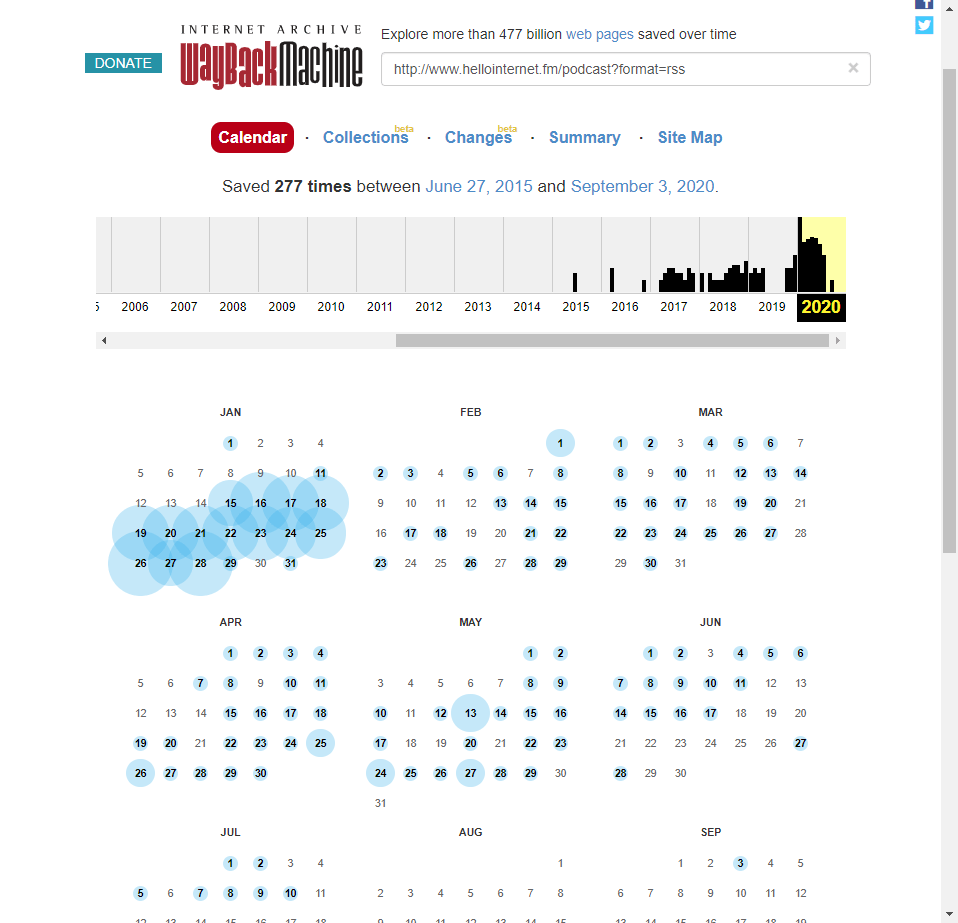

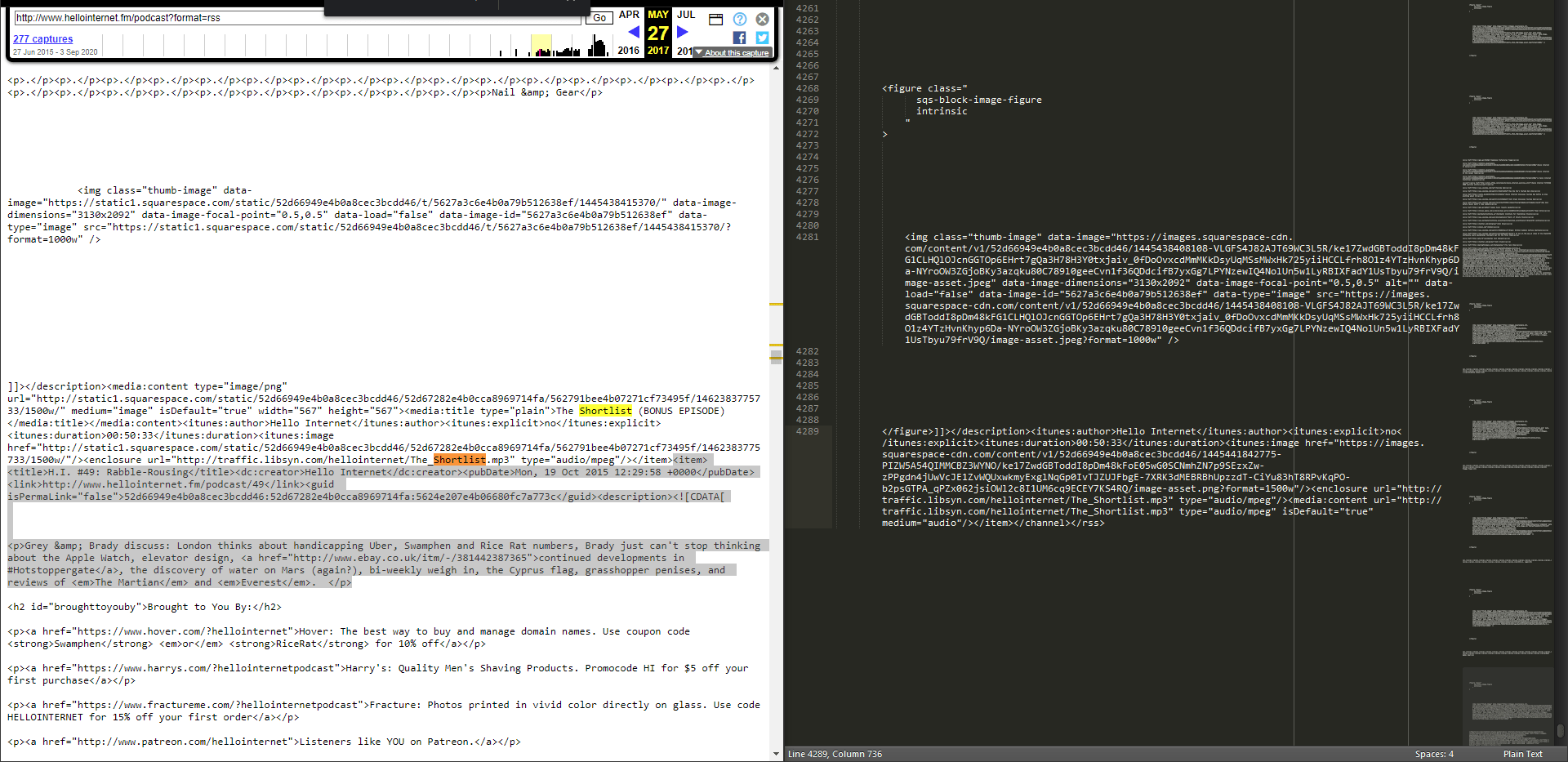

One thing you can try is searching the Wayback machine for the RSS url. If you're lucky, it will have been scraped in the past often enough so as to contain the entire history, though perhaps in piecemeal. You could download the snapshots, combine them into a single xml file, serve it out of a webserver, and temporarily point your RSS client at localhost so it ingests all those historical posts before pointing it back at the real url. Convoluted, perhaps, but I'd rather do this than inject the posts into the db myself. Then, you can pull the enclosures out of QuiteRSS's database (or from the xml file you just made).

But, in the worst case scenario, you'll find that Wayback doesn't have archives of the feed you want. At this point I write a web scraper in Python to find all the episode dates and links, or I just hit the CTRL+C, CTRL+V gym for twenty minutes, copying each link from the website manually. You may also try Xenu's Link Sleuth or HTTrack to see if they can find all of the MP3 urls automatically. I figure it's an effort I'll only have to do once as long as RSS keeps getting new posts after that.

If the podcaster has already taken the Faustian bargain, you can try using spotifeed.timdorr.com to pull Spotify as RSS, but this will give very limited history and only serves to stem the bleeding.

[1] Looks like the market has an opening for an "RSS rebroadcasting service" that archives feeds and gives clients the whole history every time.

Tagging (§)

Some podcasters add metadata to their distribution files, others don't. Most don't. At least not to my tastes. I recommend MP3Tag for tagging and renaming the files.

Tagging podcasts is a little different than tagging music. Firstly, podcasters sometimes release "bonus episodes" or "0.5" episodes, which cause track numbers to deviate from the episode number as listed in the title. Secondly, music files can usually be named artist - album - track.mp3 without much issue, but podcast titles are often much longer and contain unsafe characters like :, ?, /, etc. So, to keep things simple, I just use podcastname - releasedate.mp3 as the filename.

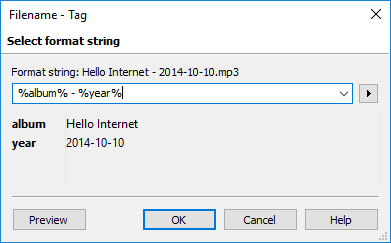

If the mp3 files don't have the ALBUM or YEAR field set, you can use MP3Tag's "filename to tag" feature to fix that.

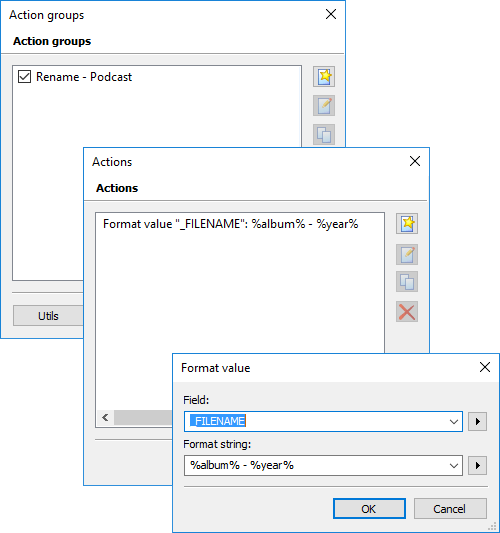

MP3Tag is great for batch renaming. In your MP3Tag actions, create a Format value action with the parameters Field=_FILENAME, Format string=%album% - %year%.

Clean up all the files' tags to your heart's content, then select them and run your rename action.

Cutting ads (§)

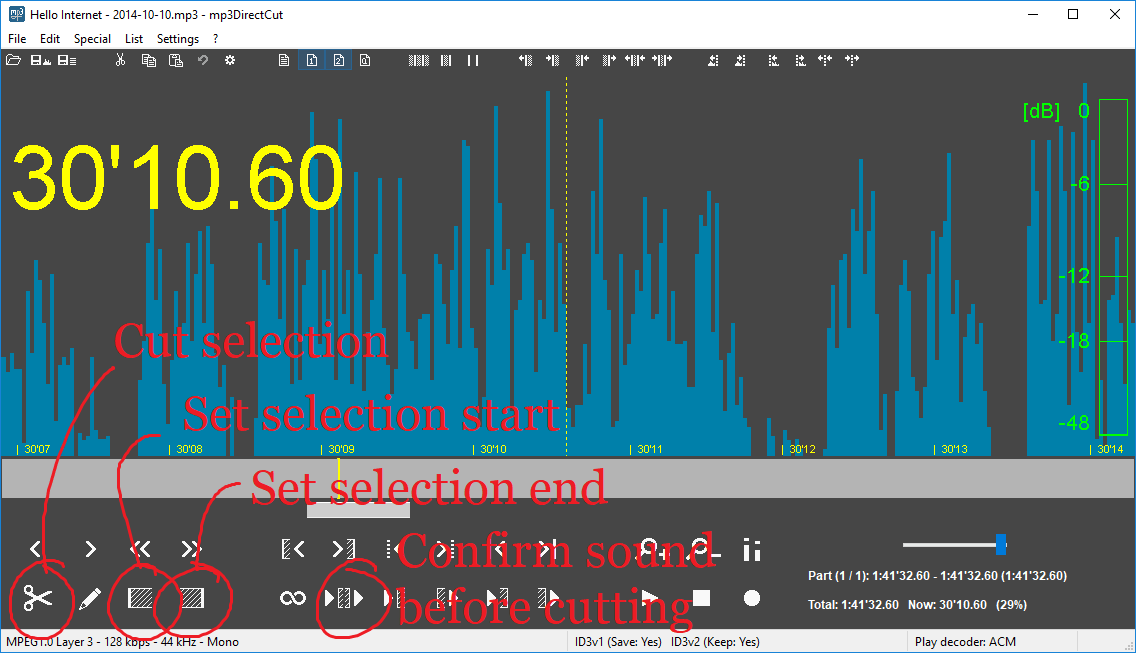

I don't listen to ads. I recommend mp3DirectCut for cutting them out. If you're going to listen to the podcasts on your PC anyway, you can kill two birds with one stone by listening to the entire podcast within mp3DC and cutting the ads as you go. If you just want to kill one bird at a time, you can skim through the file with the arrow keys and page up / page down. Most people speak differently when they read an ad, or record the ad in a separate take. You can hear these difference as you skim even when jumping 10-30 seconds at a time. Listen for differences in intonation, room noise, or long segments of a single speaker instead of the show's usual back-and-forth dialogue. You will get faster as you get familiar with the podcaster's ad spacing and speech habits.

It is important to use a tool that does lossless copying, which means it doesn't re-encode the audio when saving the new file. If you use Audacity, for example, you are loading the mp3 into a wave in memory at the beginning, then encoding that wave back to mp3 at the end. Re-encoding will cause a slight loss in quality, though I admit it will not usually be noticeable. mp3DC copies the mp3 data directly. This comes with the limitation that you can only cut at frame boundaries, but that's ok because mp3 frames are usually ~26ms long, unlike video formats where keyframes might be many seconds apart.

Listen & enjoy (§)

The final step is to rest easy in the knowledge that no one can take the show away from you at this point. You can take as much time as you need to listen through it, and it'll always be right where you left it. As it should be.

If you do not have the tools or resources to perform these steps, I wouldn't mind doing it for you once or twice. Send me an email via writing@voussoir.net.

- Replace github links with git.voussoir.net.

- Add advertixing.md.

- Move S3 images to my domain.

- Add links to Xenu, HTTrack; improve QuiteRSS db screenshots.

- Add download_podcasts.md.

If you would like to subscribe for more, add this to your RSS reader: https://voussoir.net/writing/writing.atom